|

The Passion of Christ |

|

|

The Harrowing of Hell |

|

|

King David, Abraham the

Patriarch, With many another of

his chosen nation; |

|

|

According to legend, and the Apostles

Creed, after the death of Christ, and before the resurrection, Christ

descended into Hell: |

|

|

He

descended into hell; The third day he rose again from the dead. |

|

|

I say according to legend, as the descent in to Hell, often known as the Harrowing of Hell, does not appear in any of the gospel narratives. There is an ambiguous verse in 1 Peter 3 that could refer to the event: 'For it is better, if the will of God be so, that ye suffer for well doing, than for evil doing. For Christ also hath once suffered for sins, the just for the unjust, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh, but quickened by the Spirit: By which also he went and preached unto the spirits in prison; Which sometime were disobedient, when once the longsuffering of God waited in the days of Noah, while the ark was a preparing, wherein few, that is, eight souls were saved by water.' The source of the legend is obscure, but it appeared in the writings of some of the earliest Christian theologians, such as Hippolytus and Tertullian. It was described in some detail in the 4th century apocryphal gospel of Nicodemus (supposedly by the character mentioned in John's gospel for his involvement in the burial of Christ) and in a sermon by |

|

|

|

|

|

Once the Golden Legend had appeared artists were spared reading through the Gospel of Nicodemus and the sermons of Augustine, as it provides the quotes from both. Both are lively accounts: you can read them here. |

|

|

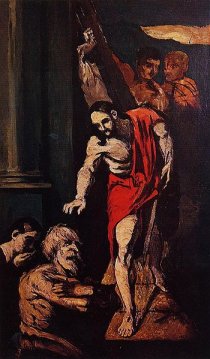

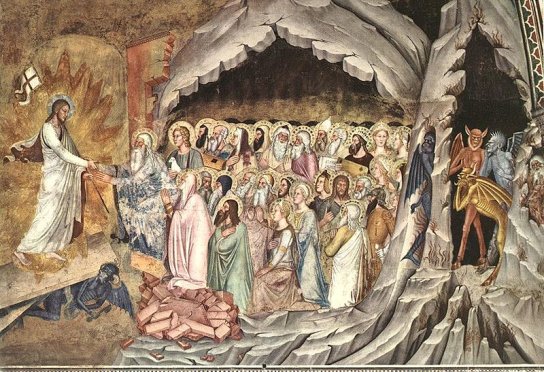

The accounts describe the arrival of Christ

in Hell, the destruction of bars and gates, and the dismay of the various

devils, who turn on Satan and accuse him of causing the trouble: ‘What prince are you? All thy gladness is perished and all thy joys are converted into tears. When you hung him on the cross you did not know what damage you would suffer in Hell.’ (St Augustine: Sermon on the Resurrection.) As Dante makes it clear, Christ did not descend in to the depths of Hell, where the sinners (and people Dante didn't like) were punished in various gruesome ways. He went no further than Limbo, the first circle. The gospel of Nicodemus describes various Biblical figures that Christ meets there. Why are they there? Limbo is for 'virtuous pagans' such as Plato and Homer, and Virgil of course, who guides Dante. It is also for the Jewish Patriarchs, and key Old Testament figures such as Adam and Eve, and King David. Isaiah is an important figure in the Nicodemus account. These were the ones released by Christ. Those pagans weren't so lucky, however virtuous they were; they were still kicking their heels in Limbo when Dante paid his visit. Sceptics may have spotted a problem with accounts of the Descent into Hell. How would anyone know what actually went on there? Christ clearly didn't tell anyone about it after the resurrection. So how come Nicodemus knew all the details? The author of the Gospel of Nicodemus had clearly spotted this anomaly, and came up with a solution that readers may or may not be convinced by. He created two characters, Carinus and Leucius, who were resurrected at the same time of Christ and were able to tell Nicodemus all about the Descent into Hell before they disappeared. These characters turned out to be the sons of Simeon, who was present at the Presentation at the Temple of the infant Christ. The painting by Cezanne shows two figures behind Christ: could these be Carinus and Leucius? Simeon speaks with Christ along with John the Baptist: they seem perhaps unlikely residents of Limbo, but as Virgil tells Dante, '. . .ere that day, No human soul had ever seen salvation.' John the Baptist is identifiable in the painting by Fra Angelico, immediately behind Adam. |

|

|

|

|

| The painting below is by the artist known as the Master of the Master of the Osservansa. It is interesting to speculate on the identity of the various characters. Adam is clearly the character greeting Christ; I would suggest that his son Seth is next to him. Could the crowned figure be King David? And could the figure with the manuscript be Isaiah? And the figure between them Eve? | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some more images. Should you have the

inclination, you could spend a long time attempting to identify the various

patriarchs in the fresco by Andrea da Firenze: for a larger image, go the

the World Gallery of art at

www.wga.hu. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|