|

The Passion of Christ |

|

|

The Last Supper - Page 5 |

|

|

In March of 2013, my wife and I took a three-day city break in Milan.

Three days is not enough, even if you don't want to go shopping for

shoes and handbags. There's the Brera, of course, the Duomo, and some

wonderful churches. The Pinacoteca Ambrosiana is a gallery that

shouldn't be missed. While we were there we managed two visits to Santa Maria delle Grazie to see the Last Supper, once by ourselves and once as part of a Milan day tour complete with guide. As my surreptitiously taken photograph below shows, the substantially rebuilt refectory is now a tourist venue, and most of the physical context has been lost. |

|

|

|

|

|

Let's have a better look at what's left of the painting: |

|

|

|

|

|

According to Steinberg, the limited, secular interpretation of the painting started with Goethe. In his essay on the picture published in 1817 he described it in psychological terms; the disciples were reacting to the news of the betrayal - shock, incredulity, and so on. That was it. Steinberg points out that Goethe had only seen the real thing very briefly, and he relied for his essay on an engraving of the painting that omitted one or two key details. So perhaps Goethe cannot be blamed entirely. (His Italian Journey is one of my all time favourites; Goethe often comes over as rather serious and grim, but this book shows that he did have a considerable sense of humour.) Steinberg also suggests that Goethe's interpretation was part and parcel of the nineteenth century's secularism and 'aversion to ambiguity' as he puts it. Steinberg suggests that this view has now been superseded. It is now recognised, he tells us, that this is a multi-layered image with the Eucharist at its heart. This is somewhat over-optimistic. The Wikipedia article on the Last Supper focuses entirely on the 'Psychic shock' angle. So did the Milanese guide who talked us through the painting on our second visit. There is much to be said about the painting and Steinberg's extensive analysis of it. I am going to look only at a couple of elements of the picture. For more, read Steinberg, or follow this link to my good friend Frank DeStefano's excellent review of it , first published on the Three Pipe Problem Blog in May 2012. Multilayered? So what are the layers of meaning that go beyond Goethe's pyschological shock? We'll deal with two here, both drawn from the hand gestures of the disciples. The first layer references the individual disciples themselves. We've already mentioned Peter's knife that prefigures later events. The second reference is to the sacred meaning of the Last Supper itself. |

|

|

|

|

|

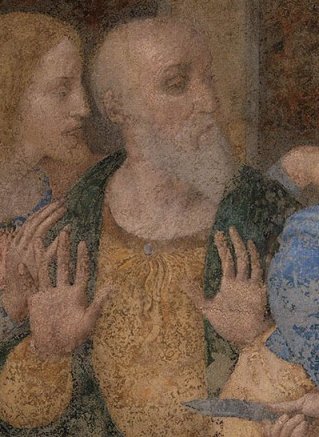

Above are Thomas (left) and Andrew (Right). Let's deal with Thomas first. The finger pointing upwards is a familiar one in art and certainly can't be considered any sort of psychological reaction. Below is another Leonardo, work, his John the Baptist of 1513 - 16. The finger does, of course, have significance for Thomas - he used it to confirm the resurrection of Christ. It has a broader meaning: the finger points to heaven and foreshadows the Ascension to come. |

|

|

|

|

|

It is more understandable if Andrew's raised hands are seen as an expression of alarm, and this is how the gesture is often viewed; but, as Steinberg points out, the calm face doesn't match. On an individual level, it can foreshadow Andrew's own crucifixion. The broader meaning is more complex. The gesture is very old; in Roman catacombs 'orant' figures are shown in this pose, an attitude of prayer that represented Christ on the cross. It is still a familiar priestly gesture as part of the Eucharist. And . . . we have seen it before. Remember this detail from Lorenzo Monaco on the last page? (bottom left). I asked you to look at the disciple on the right of the picture. Leonardo wasn't the first. |

|

|

|

|

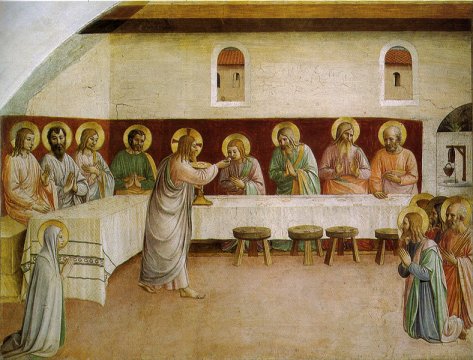

| Just one more picture that relates to this - and it isn't a Last Supper at all, though that surely is its inspiration. It is one of the wonderful frescos in the Convent of San Marco in Florence by Fra Angelico, or in this case, probably by one of his assistants, from 1441-42. This is from cell 35. | |

|

|

|

|

The scene is San Marco - the architecture is unmistakeable. A group of Apostles are receiving the bread and wine from Christ himself. Look at the hand gestures - especially the second seated disciple counting from the right. Certainly not an expression of alarm. There is a further consideration that can be drawn from this picture, one that Steinberg doesn't really pick up on, but perhaps should have done. San Marco was a Dominican Convent, and devotion to the Eucharist was a vital part of their theology and practice, exemplified in the importance with which the feast of Corpus Dominii was regarded. Santa Maria delle Grazie was a Dominican convent too. Not making the Eucharist the central concern of the painting would have been unthinkable. So that wraps it up? Well, not quite. In 2004 (three years after Steinberg's book) Michael Ladwein published Leonardo Da Vinci, The Last Supper: A Cosmic Drama and an Act of Redemption. I mentioned this book before in relation to catacomb images. What Ladwein does is effectively rehabilitate Goethe. 'This first generalised announcement of the betrayal in which the identity of the traitor is not yet revealed is what Goethe described as the 'means of bringing about the agitation' which results in the lively play of gestures and expressions among the apostles. Each one of the twelve reacts in his own way to this enormity, depending on his character, temperament and age, or in keeping with his particular relationship with Christ' It has to be said straight away that Ladwein does recognise that the disciples gestures can go beyond mere shock. He also recognises the Eucharistic elements, though the focus here is more on the arrangement and geometry of the picture, which is important in Steinberg's book also. But agitation comes first. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Steinberg's book is mentioned only in the bibliography and in a brief footnote in Ladwein's book. Spats between academics is not what this site is about so we won't pursue that one! So where does the truth lie? Maybe we should say that Leonardo was so much greater than all of us, and we shouldn't discount anything. Ladwein quotes Rudolph Steiner who said that this painting 'revealed the meaning of Earth existence.' A good note to finish the page on. |

|